Room of the Fire in the Borgo — Raphael's Third Vatican Chamber

- The Museum

- Raphael's Rooms

- Room of the Fire in the Borgo

Fire in the Borgo

Fire in the Borgo

The Room of the Fire in the Borgo is the third room Raphael painted in the Vatican palaces, after the Segnatura and Heliodorus rooms. Pope Julius II, who had commissioned the latter two, died in 1513 and the project was inherited by his successor, Leo X, not without some significant changes.

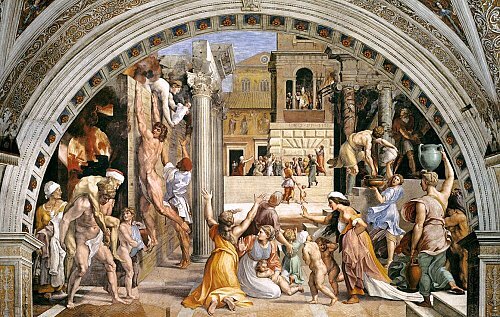

The iconographic programme promoted by the pontiff on this occasion was less affected by the spiritual and political tensions that had underpinned the decoration of the two previous rooms. The frescoes are not related to the function of the room they decorate (perhaps originally the papal dining room), but celebrate the reigning pope in courtly tones by glorifying the exploits of two of his illustrious predecessors with the same name: Leo III and Leo IV. The scene of the Incendio di Borgo (Burning of the Borough) illustrates a miraculous event that took place during the pontificate of Leo IV. A fire broke out among the wooden houses of the Roman district of Borgo, close to the Vatican. Despite attempts to extinguish it and the mobilisation of the population, the flames seemed uncontrollable until the Pope appeared from his palace and, with his blessing, managed to extinguish the blaze.

Raphael worked intermittently on the Stanza dell'Incendio (Room of Fire) from 1514 to 1517. Busy with countless other papal commissions and tasks of great responsibility, including that of architect of the new St Peter's Basilica, the Master intervened very rarely in person and almost exclusively in the fresco depicting the fire, not coincidentally the one that gave the entire room its name.

Instead, he entrusted his workshop with the task of completing the remaining three scenes; in some cases this was done on the basis of drawings and studies he had made himself, while in others Raphael allowed his collaborators greater freedom, which did not always lead to consistent results in terms of quality.

The scene lacks a unified architectural setting capable of containing the numerous figures, as was the case in the School of Athens.

In this case, we are faced with three distinct backdrops, which seem to slide like theatre wings on a common stage.

They provide a general, almost symbolic reference to history, but do not constitute a realistic setting.

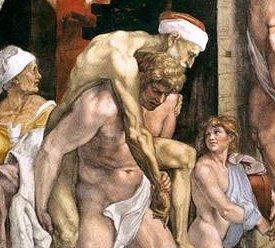

Like the settings, the characters do not form a homogeneous whole. Raphael focused on the individual figures, staging a wide range of accentuated movements, lingering on the description of their naked bodies and exploring their different emotions.

Note, for example, the astonishment of the woman in the foreground who is witnessing the miracle with her mouth literally agape.

The group of refugees on the left is inspired by the story of Aeneas, who fled Troy in flames, carrying his elderly father Anchises on his shoulders and his young son Ascanius.

This detail is Raphael's tribute to the ancient world.

Battle of Ostia

Battle of Ostia

Battle of Ostia

The Battle of Ostia, in which the troops of Leo IV (pontiff from 847 to 855) faced off against the Saracen hordes in 849, celebrates the miraculous victory of the papal armies and also refers to the crusade against the infidels promoted by Pope Leo X (pontiff from 1513 to 1521).

The Battle of Ostia depicts the victory of the papal galleys over the Saracen fleet during an attack on the port of Ostia in 849. In the fresco, the Pope, on the left and giving thanks, has the features of Leo X, alluding to a crusade he had vainly called for against the Ottoman Turks. On the right, in the foreground, we see some Muslim prisoners being disembarked and brutally brought before the pontiff, where they kneel in submission, a theme derived from Roman art known as dei captivi.

Raphael is usually credited only with portraits of the Pope and cardinals.

Crowning of Charlemagne

Crowning of Charlemagne

Crowning of Charlemagne

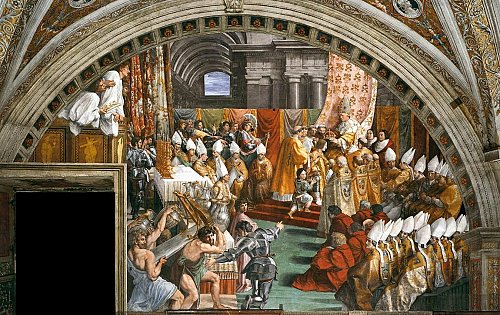

The Holy Roman Empire finds its place in the coronation of Charles the Great, which took place in St Peter's at sunset on Christmas Eve in 800.

It is very likely that this fresco refers to the Concordat drawn up in 1515 between the Holy See and the Kingdom of France, since Leo III, who was pontiff between 795 and 816, appears here under the features of Leo X, while Charlemagne comes under those of Francis I.

The coronation of Charlemagne by Leo III took place on Christmas Eve 800 in the ancient Basilica of St Peter's, Vatican, probably referring to the Concordat of Bologna, a treaty signed in 1515 in Bologna between the Holy See and the Kingdom of France. In this fresco, the Pope has been made to look like Leo X, while the Emperor is based on Francis I, who happened to be King of France at the time of the painting.

There was little personal input from the master on this work, as its execution depended largely on his pupils. It is arranged on a diagonal axis that leads the eye into the depths where, under the papal canopy decorated with the keys of St Peter, the coronation itself takes place. This is in an auditorium surrounded by two wings of cardinals, bishops and soldiers.

In the foreground on the left, a group of servants are busy arranging large silver and gold vases and a golden-legged shelf on an offering table, echoing the Roman imperial motif of triumphal processions.

Justification of Leo III

Justification of Leo III

Justification of Leo III

The Justification of Leo III depicts an event that took place on the eve of Charlemagne's coronation, during which the Pope responded to the slanders spread by the nephews of his predecessor, Hadrian I, by reaffirming the principle that the Vicar of Christ is solely accountable to God for his actions.

The mural, created entirely by the students, celebrates the oath taken in the ancient Basilica of St Peter's on 23 December 800, in which Leo III absolved himself, “without compulsion and without being judged by anyone” from the false accusations made by the nephews of Adrian I, just one day before Charlemagne's coronation. As in the other frescoes in the chamber, the Pope is depicted as resembling Leo X.

Echoing from above were the words inscribed on the scroll below, “Dei non hominum est episcopos iudicare,” which translates as “It is for God, not man, to judge bishops.” This statement clearly refers to the endorsement by the Third Lateran Council in 1516 of Boniface VIII's bull Unam sanctam, which established the principle that only God can judge the responsibilities of the Pope[7]. The text is derived from the structure of the Mass of Bolsena.

Ceiling

In 1508, Pope Julius II (reigned 1503-13) commissioned Pietro Vannucci (known as Perugino) to paint the ceiling.

The iconographic scheme relates to the function of the room at the time of Julius II, when it was used for the sessions of the Supreme Court of the Holy See, known as the Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae, over which he would have presided. In fact, Perugino illustrated in these four medallions what was usually described as the Sol Justitiae - elements including the Creator seated among angels and cherubim, Christ being tempted by the Devil, and Christ between Mercy and Justice.

Perugino's vault depicts themes of the Trinity. In rich grotesques with gold backgrounds, scenes include the Father with angels and cherubs, Christ between Mercy and Justice, the Trinity with the Apostles, Christ as Sol Iustitiae, and Christ being tempted by the Devil. Decorative taste reigns here with symmetry and great horror vacui - in fact, every possible space is filled with angels, cherubs and seraphim - soft colours in soft pastel tones against a strong blue background and the dominant gold embellishments surrounding the decoration.

Because of their association with different ornamental styles, there is no particular relationship between the medallions in the vault and the scenes in the large lunettes below.